It might seem strange that I, a 25-year California resident, love Alabama. Even more improbably, I can trace it all back to high school and my cousin, Petrea, a blond Californian valley girl who, at the time, was more interested in crashing college parties than civil rights. One scorching summer in 1988, she, her brother Noah, my sister Eunice and I pedaled over to CD Research, a brand new music store in Davis selling something called a CD – the latest in cutting-edge technology.

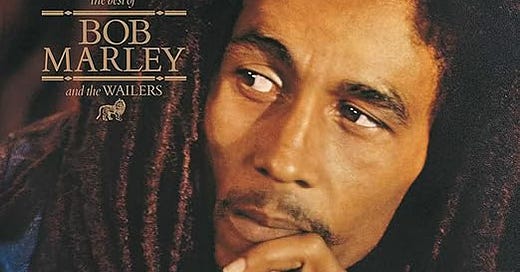

In that modern worship hall, we clacked through the plastic cases, slipped squishy headphones over our ears, and listened. That’s when I first heard Bob Marley and the Wailers. Their album Legend was the first CD I ever bought.

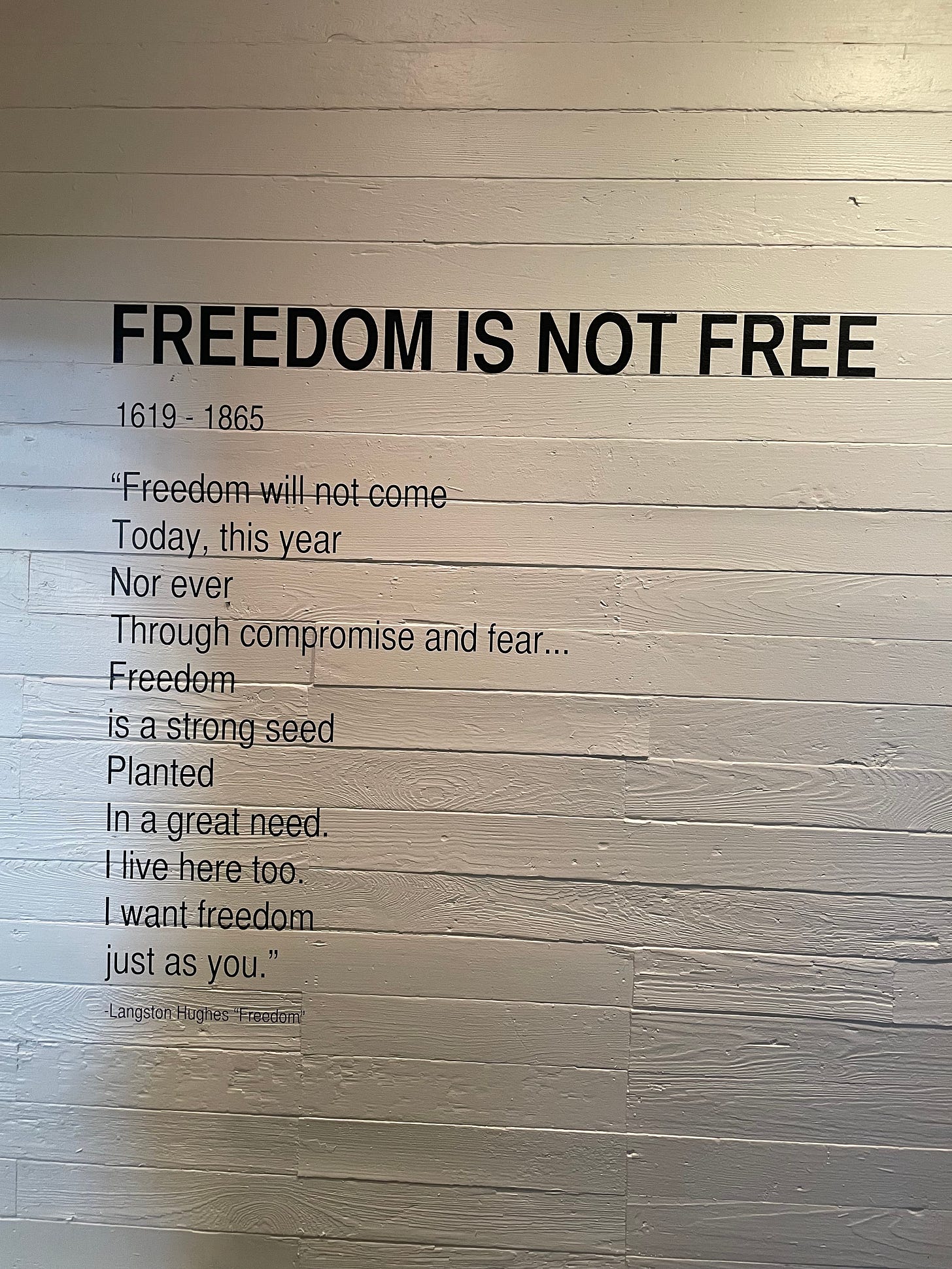

The song that moved me the most was Redemption Song, specifically the lyrics, “emancipate yourselves from mental slavery, none but ourselves can free our minds.” It pounded my heart as some kind of truth, though I had no idea what it meant.

The First Roadtrip: Epictetus and Elvis

In 2000, I picked up the phone. I was in my 20s, living in Somerville, MA. It was Petrea. She had just landed an environmental consulting job in Sacramento (turns out this California valley girl is a total bad-ass!). I had just been accepted to Stanford Business School. Did I want to drive cross-country with her, back to California? A few weeks later, she was standing on the decaying front step of the Victorian I shared with five roommates. We crammed my worldly possessions into my VW Golf, including a vintage sled that proceeded to hurtle forward and decapitate us every time I tapped the brakes over the next 3,000 miles.

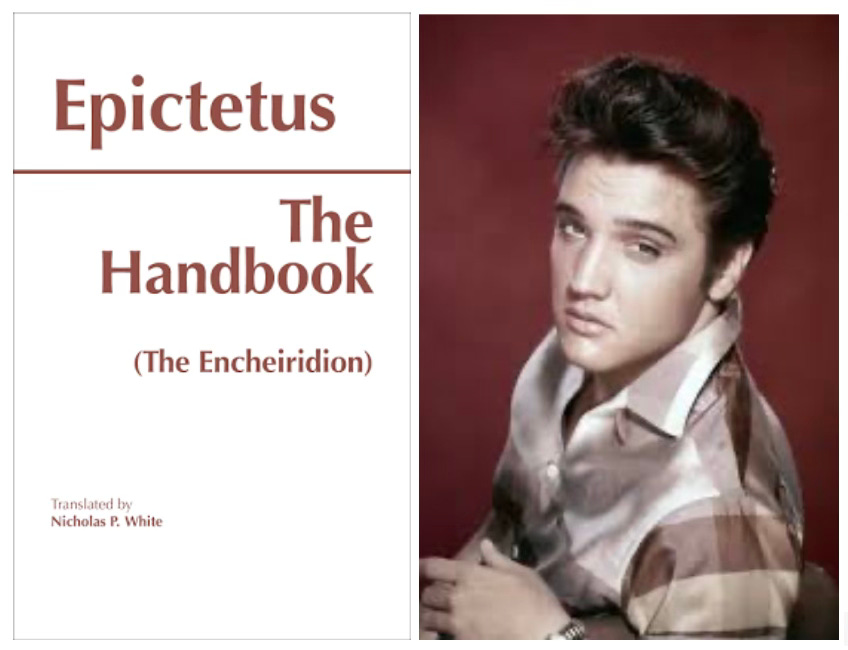

Tucked next to my parking brake was a slim volume of Epictetus: The Handbook, by the Stoic philosopher and Roman slave, a parting gift from my friend Colin, a philosophy Phd student. Colin, a stern and somber but wryly funny guy, loved to ask deep questions like “What does it mean to lead a good life?” At college parties, he would interrogate attractive women about their values and views on marriage and children, making my job as wing woman exceedingly difficult.

Petrea and I were scattered with nerves and anxiety. We quickly fell into a self-soothing ritual of reading Epitetus aloud as we drove, belting out Elvis at the top of our lungs whenever we needed a power-up. Bizarrely, Elvis and Epictetus seemed to have slavery in common, as evidenced by Elvis’ Teddy Bear:

Oh, baby let me be, your lovin' teddy bear

Put a chain around my neck, and lead me anywhere

Oh, let me be (oh, let him be)

Your teddy bear

Unlike Epictetus, Elvis was far from emancipated.

After ten nights and ten days, we emerged from the wilderness of The White Mountains, The Adirondacks, Glacier National Park, and The Badlands, and pulled into Petrea’s childhood home in Davis. Our minds felt free and clear.

Petrea invited me to check out her new apartment and meet her roommate, John Dorsey, a college friend and medical resident at U.C. Davis. John had already moved in, but you couldn’t tell. He lived like Epictetus. Suffice to say there was no vintage sled to be seen.

A few years later, as John tells it, he found himself in rural Alabama in a storm. His job at a local hospital had just been canceled. Rather than leave, he took it as a sign. He checked into a motel and asked the clerk if there were any nice towns nearby. The clerk pointed him to Greensboro, population 2,500. John moved there and founded Project Horseshoe Farm, a community health non-profit that provides everything from afterschool activities for kids to Bingo nights to housing and elder home visits. When I showed up to visit for the years later, I would discover that, as improbable as it may sound, John is now the de facto mayor of Greensboro.

The Second Road Trip: Alabama Dreaming

In 2021, I picked up the phone. I was in my 40s, living in San Francisco, raising three boys. It was Petrea again. She had just come back from Alabama with her teenage daughter. “Alabama?!” I said in disbelief. “WTF were you doing in Alabama?” She said, “Well, we were doing a slavery and civil rights tour. And visiting John Dorsey.”

Petrea is an industrious traveler and she had researched the crap out of the Civil Rights Trail, a National Parks website that tells you about all the civil rights sites across the United States. She had then taken it upon herself to organize a trip to visit some of these sites, and to take her daughter along with her. I’m less industrious, so after glancing at the website, I picked up the phone and called my travel agent. Could she help me organize a 1-1 mother-son civil rights trip? “Sure,” she said. A couple months later, we were on a flight to Atlanta to begin our journey (spoiler: there are no direct flights from San Francisco to Alabama).

What blew me away about going to Alabama was not the sights, but the people. It was and is the fact that there are still so many people alive who were young activists involved in the Civil Rights movement. This is remarkable because they have so much perspective – I had no idea that this living history was all around us. And I had no idea there were so many people continuing to advance the legacy of civil rights and social justice in Alabama today.The first such person was John Key, at a non-profit called Alabama Civil Rights Tourism. They mostly cater to large groups of college alumni, but John was kind enough to take us on and design an itinerary for us.

The second person was the driver and guide that John connected us with. His name is Willie Williams, and he is an arts educator and choral director who lives in Atlanta. He is a warm, wonderful and generous man, and, as we navigated highways and backroads, he was kind to tell me about his experience growing up there, dispelling some of the stereotypes that I had about the South, while at the same time sharing stories about how segregation and racism is still very much alive and well in Alabama, as it is through the United States and the world. It was such a gift to be able to spend hours talking to Willie as we crossed Alabama.

Tuskegee

Our first stop was the Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site, in Tuskegee, where we got to meet with a lovely National Parks Ranger who told us the stories of the accomplished Black airmen who served in World War II. Their achievements are credited with motivating the U.S. to integrate the military. We also swung by Tuskegee University, founded by Booker T. Washington and where George Washington Carver, a Black inventor and renaissance man made his reputation. There was something profound about just walking on the soil of a historically Black college that had been founded in 1881, just after the Civil War.

Montgomery

Our next step was Montgomery. While we didn’t get to meet him in person, Bryan Stevenson, the public interest lawyer best known for his book Just Mercy, looms large in Montgomery. He created the Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice.

With its rows of suspended blocks carved with the names of lynching victims, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice stands as a visceral and immersive memorial of loss rivaling the Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial in Washington, D.C.

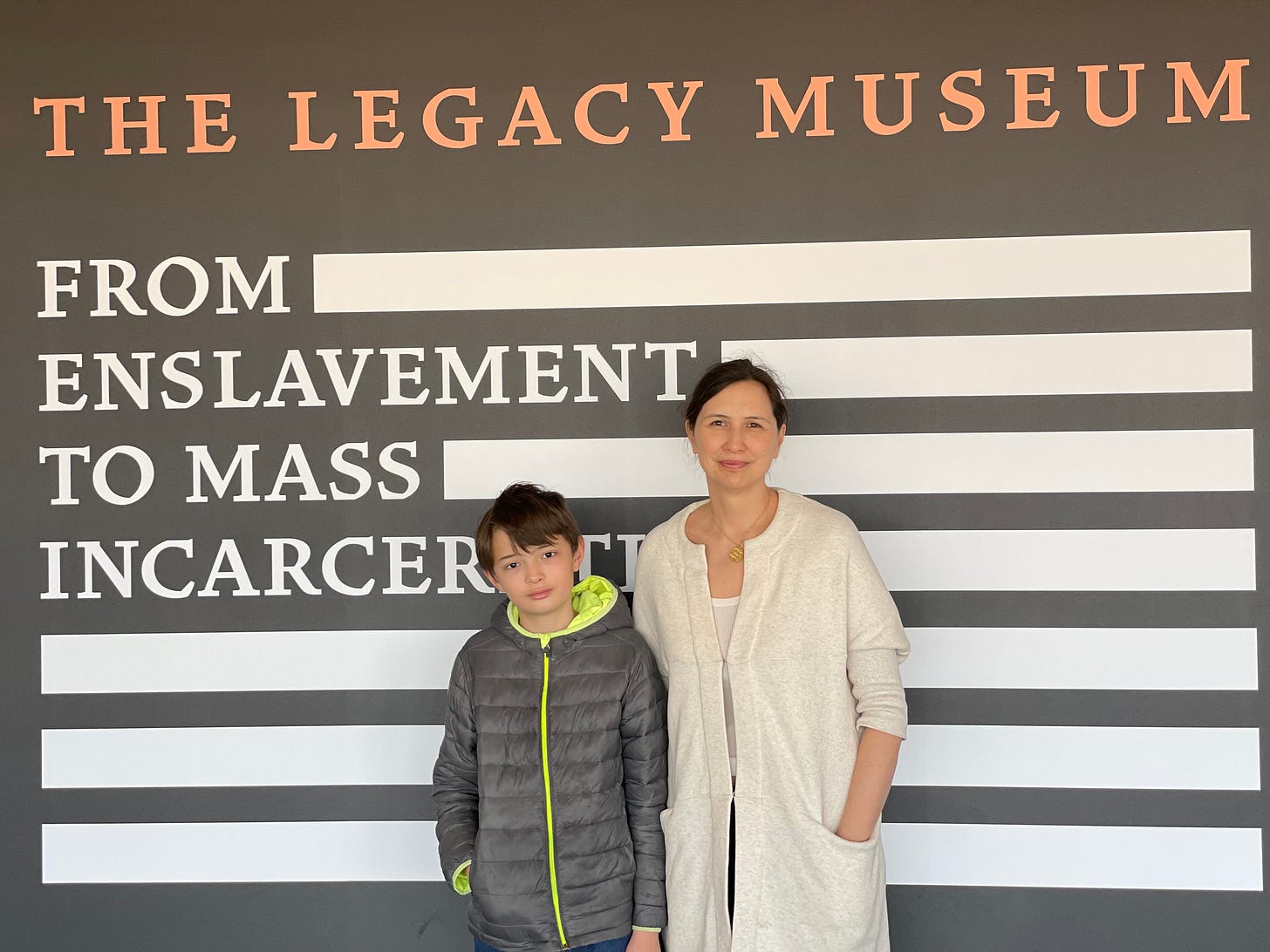

The Legacy Museum is dedicated to helping people experience the journey of African Americans from the Middle Passage and slavery to mass incarceration, and ends with a beautiful and poignant reflection room of Black artists and luminaries – allowing visitors to reflect on how pain and suffering, in no way justified, has given birth to Black excellence.

Speaking of excellence, we got to meet the inimitable Wanda Battle, a modern-day griot who simply beams with loving energy, and a steward of the Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church, nestled along the avenue that connects the Alabama State House to the central plaza in Montgomery that used to be its slave market. Surrounded by beautiful dogwood trees, Martin Lurther King, Jr. often gave sermons here. Wanda unlocked the door, welcomed us into the empty sanctuary, and sang her favorite spirituals while my son stood awestruck at the pulpit, the lights shining through the stained glass windows with ethereal transcendence.

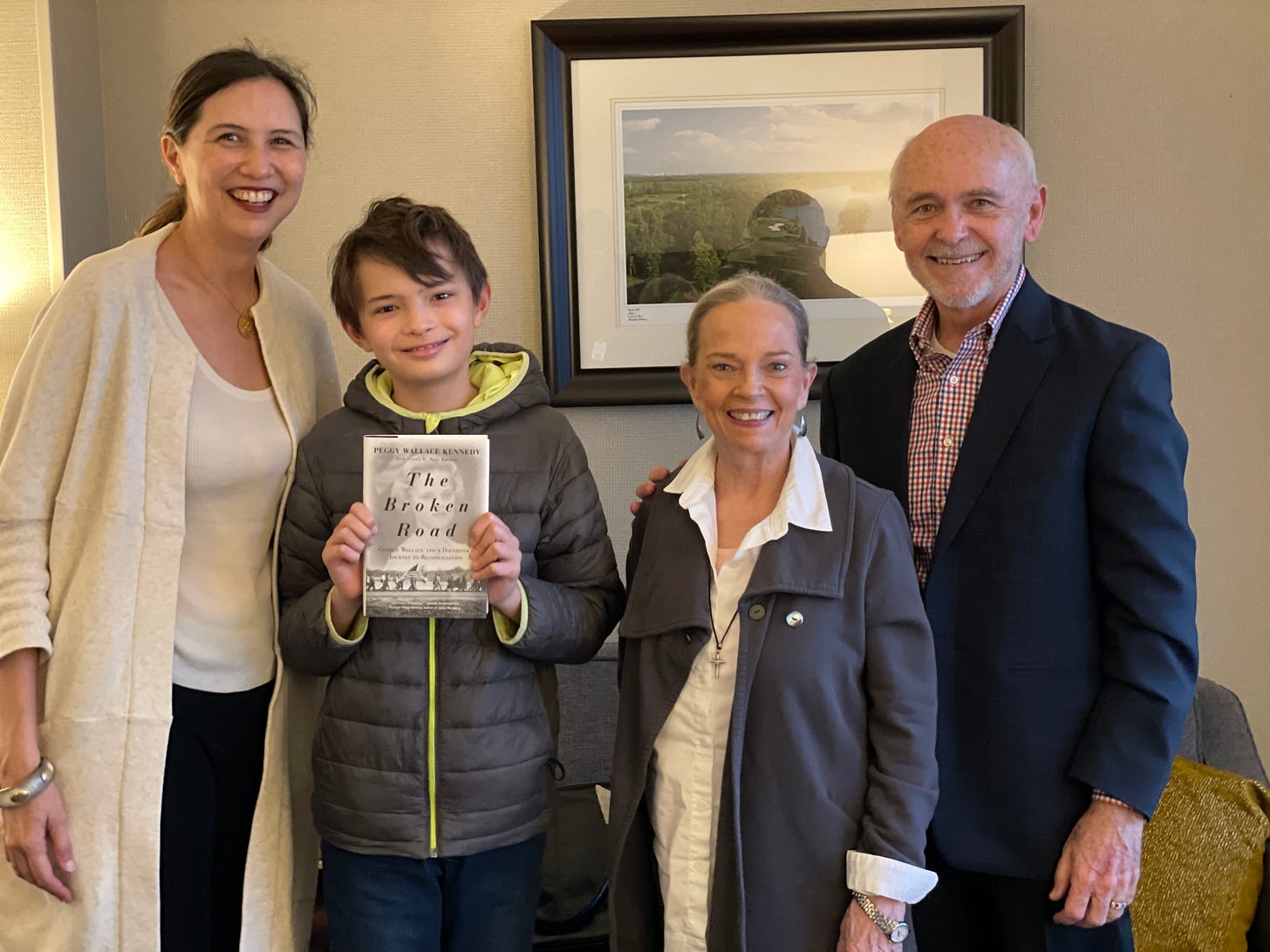

Next, we met Peggy Wallace Kennedy, the daughter of the former Alabama Governor George Wallace, who infamously stood in the school house door and declared “segregation now, segregation forever.” She is in her 70s now and married to retired Alabama Supreme Court Justice Mark Kennedy. Her riveting story is detailed in her memoir, The Broken Road, and we got to meet with her in our hotel room, where she told the story of her childhood and her journey of reconciliation and redemption of her father’s legacy and how she has worked so hard to repair the damage her father had done. One of her best friends was the late John Lewis.

Birmingham

Following Montgomery, Willie drove us to Birmingham, where we met two more incredible women.

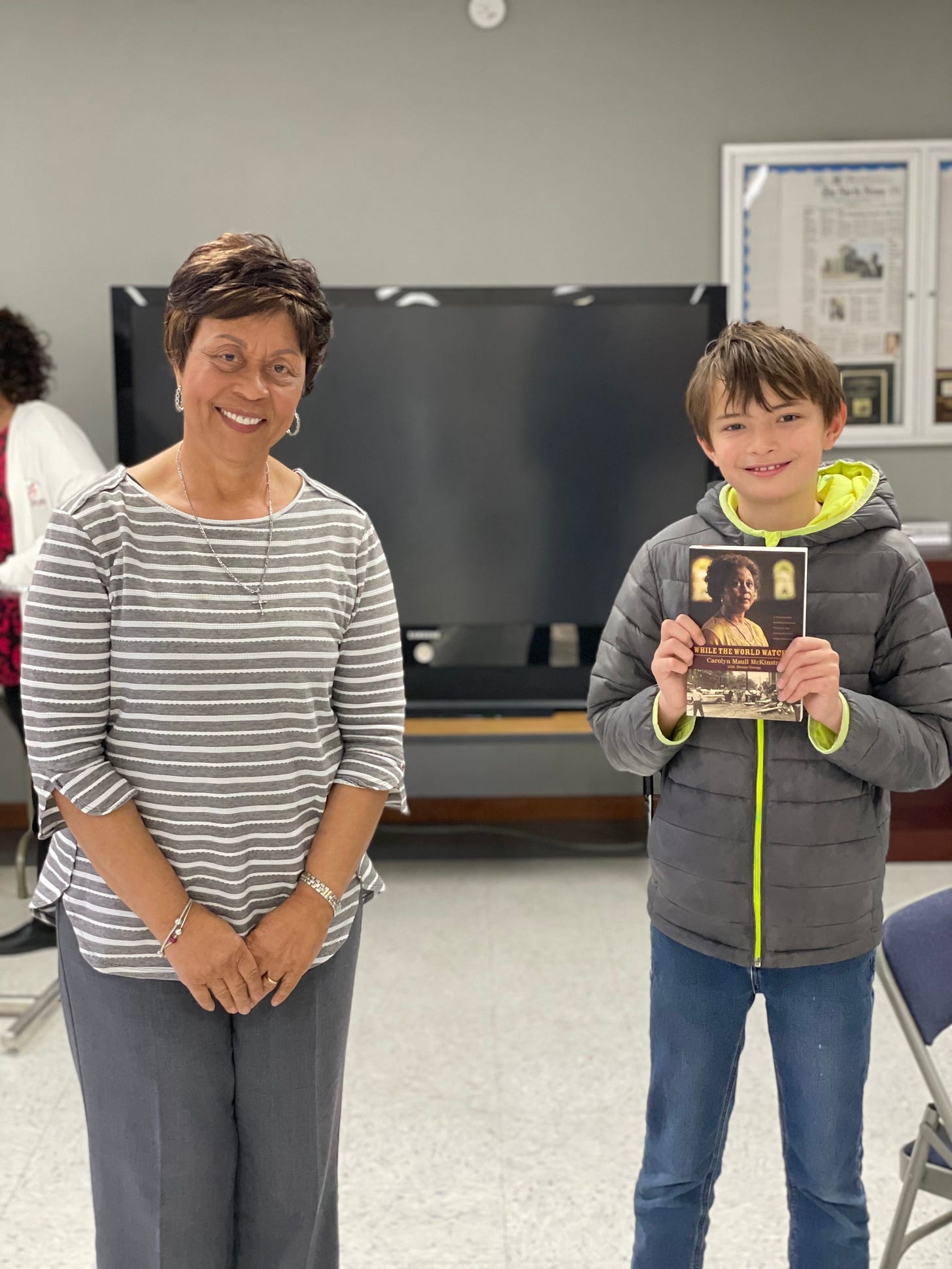

The first was Carolyn McKinstry, who survived the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing and met with us at the historic Bethel Baptist Church. Quietly and intently, she sat down with my son to tell him about her experience that day when, at the age of 15, she went to church and her good friend was killed in the bombing. James listened to her with rapt attention. She also gave him a copy of her memoir. I was struck by her grace and presence.

The second was Dr. Martha Bouyer, an educator and curriculum developer who specializes in civil rights education. We met her at the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, where she made the exhibition come alive, asking my son engaging questions, and walking us through the plaza opposite it, where protesters had been attacked with dogs and fire hoses.

Civil Rights and Social Change: Past, Present and Future

My first trip to Alabama was transformational in helping me understand the physical enslavement of Black Americans, the segregation and violence of Jim Crow that preceded the Civil Rights movement, and the transcendent forces that aligned to allow Martin Luther King, Jr. and his associates to create major social change. It was inspiring to walk the ground where that organizing had happened, while at the same time recognizing that a lot of the issues that they fought about are still present in our society, and they are much more ethereal and difficult to pin down today.

My second trip, the following year with my second twin son, helped me understand the role of mental liberation in the civil rights movement. This time, we went to Selma to visit with JoAnne Bland, one of the young people who marched across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma. JoAnne says that in today’s world, the quest for civil rights and respect for Black people is much more elusive. The actions of the Jim Crow era were more obvious and blatant. Change was easier due to a more concentrated media. In today’s fragmented, rapidly changing, and reactionary society, sustained collective action of any kind is more difficult.

JoAnne’s words were sobering, and inspiring. She and her peers are not daunted by the challenges. In many ways, they have all arrived at the same place as Marcus Garvey: emancipating your mind. Freedom starts with liberating ourselves from internal suffering that we impose on ourselves in part by insisting other people change or rescue us. Forging reciprocal and authentic connection is one thing, judging and directing others without their consent is entirely another. In Gandhi’s words, the only option we have is to be the change that we want to see, and to light the way for others by serving as a template. At the same time, we need to understand systems and recognize injustice. Once you change yourself, you can work collaboratively with others who share the same emancipated mindset.

I could see this in what appears to be a new model for social change that is playing out in Alabama today: one that is individual, local, and deep. It shows up in the way that Bryan Stevenson is transforming Montgomery, creating educational institutions and monuments for learning and reflection. It also shows up in the way John Dorsey is transforming Greensboro by weaving himself into the fabric of that community, one relationship at a time; many others are now seeking to replicate what John has done. Change is local, and it is centered around people. One person at a time can truly make a difference, and true change must be deeply rooted in people and community.

Sweet Home Alabama

As I write this, I am planning my fourth trip to Alabama, with my youngest son and his grandparents. Last year, I took my third, where I visited John Dorsey for a second time with Petrea and her daughter, and made biscuits with Chef Scott Peacock, in Marion, who is building community through cooking inspired by his former mentor and companion, renowned Black chef Edna Lewis. I am deeply looking forward to it.

I recently read that many Black people are moving back to the South from places like California. I can understand why. For one, the Alabama countryside, or “Black Belt” as it is known, for its rich, fertile soil, is beautiful, and the cities are as well – not to mention more affordable. For another, as the birthplace of the Civil Rights movement, Black history and monuments are all around. As Isabelle Wilkerson documented in The Warmth of Other Suns, during the Great Migration, massive numbers of Black people migrated to the North and West from the South to escape Jim Crow and seek better economic opportunities; yet, the same problems of segregation and racism greeted them there. In Alabama, however, the soil is rooted in Black experience, buildings all around were built by enslaved and free Black people, and the spirits and legacies of many of America’s most esteemed visionaries and leaders – past and present – are everywhere.

Have you seen the new Selma to Montgomery march museum , that is in Selma it’s really good, I hope government cut backs do not shut it down.

I am from Alabama, yet in the pat twenty five years I have been traveling the country. And there seems to be more racism, in rural Pennsylvania and New York than Alabama .