Recently, I wrote about how “I’m not a writer” is a deep cut, an old story I’ve been telling myself since childhood. Substack and this community of writers is the thing that finally broke the story – so thank you for being here! You all are. The. Best.

Today, we’re going to dig into where negative stories come from and how to get out of them. This is a huge topic – entire religions and self-help empires are built around it! – but I’m going to do my best to synthesize what I’ve learned over 20+ years of working on my own stories, raising children, and being on a mission, through Hello!Lucky, to spread joy, creativity, and connection.

Let’s dive in . . . this is heroic work, and it’s going to take guts.

The vulnerability of children

The first thing to notice is that negative, self-sabotaging stories typically take root when we are the most vulnerable – as children. If we were present, well-resourced, and able to self-advocate, we wouldn’t let them. Unfortunately, as children, we are not. We are dependent, naive, and vulnerable, and don’t have a strong sense of what stories are “mine” vs. “not mine” – which is maybe why, from an evolutionary standpoint, one of the first things toddlers start to learn is “mine!”

Negative stories typically ride on the coat tails of emotional wounding. In my case, “I’m not a writer” was a subset of a bigger story I told myself: “I don’t deserve to have a voice.” My dad had a dark sense of humor and used to call out “Hey, stupid!” to see if I’d react (his twisted version of “made you look!”), or wryly quip “Children should be seen and not heard” when my sister and I were boisterous. My mom, an artist at heart, wielded criticism like a sculpting tool – attempting to shape us and reveal the masterpiece in the slab of marble.

Emotional wounds vs. physical wounds

In his TED talk and book Emotional First Aid, psychologist Guy Winch astutely observes that emotional wounds are just like physical ones – but instead of on the outside, they’re on the inside. A broken arm is impossible to ignore. We obligingly take the patient to the emergency room, set it in a cast, and tell them to rest. If the person is emotionally wounded, however, we turn the other cheek. We might even patronizingly dismiss the symptoms (acting out, withdrawing, insecurity, etc.) as inevitable personality traits or signs of weakness. “Oh, that Petunia was just born with a bad leg.” In reality, emotional wounds can be just as deep and harmful as physical ones.

The five childhood safety patterns

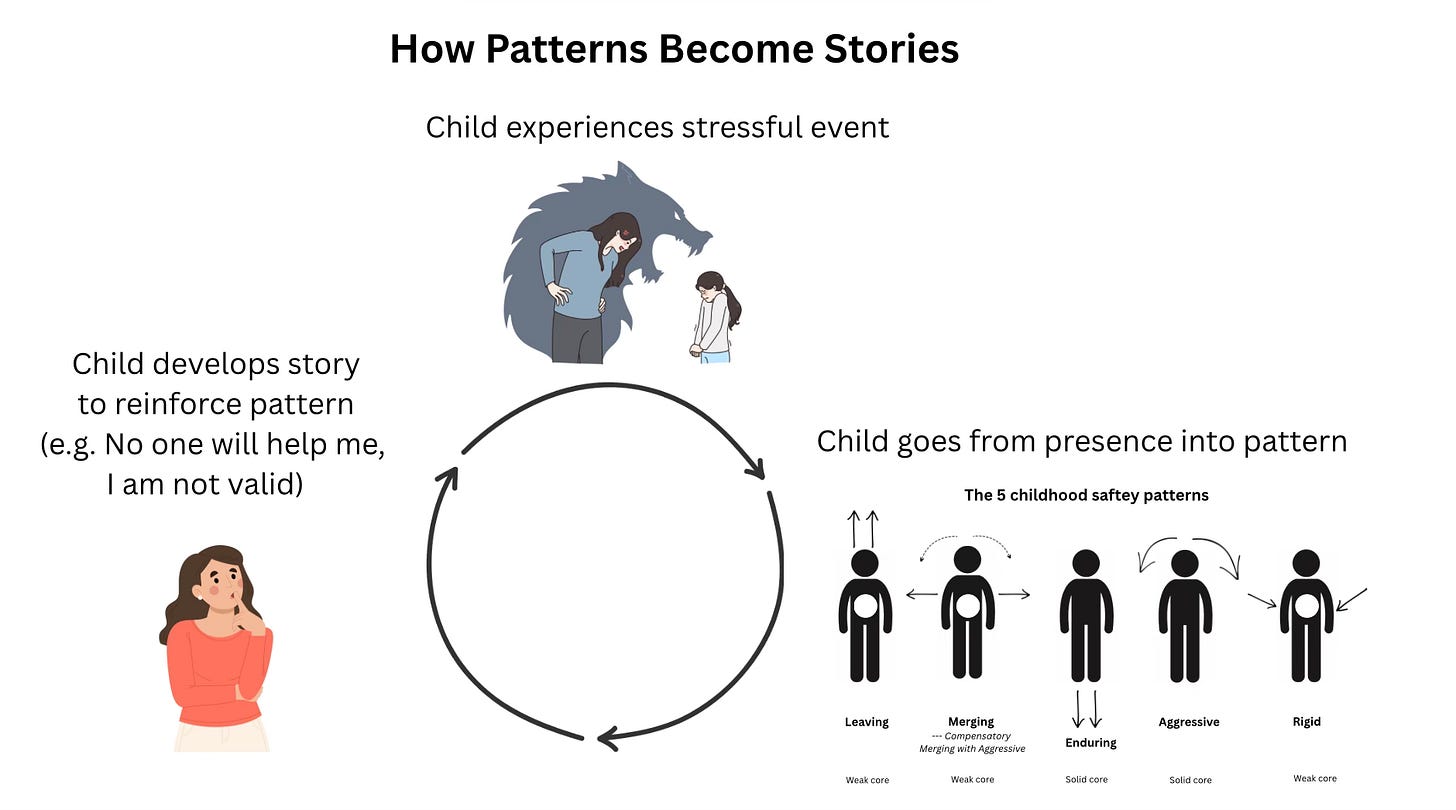

This may sound outlandish, but self-sabotaging stories are actually attempts to stay safe. Infants and toddlers have no verbal skills and crap themselves constantly. As a result, they learn to keep themselves safe by directing their attention and energy, rather than using words.

There are five basic ways children learn to direct their energy, called the 5 safety patterns (Kessler, 2015 & 2024). They are:

Leaving - the child’s energy leaves their body into the intellectual, creative, or spirit dimension. Energy moves up and out of the body, a form of dissociation. The child does not develop a strong energetic core or boundaries.

Merging - the child’s energy merges with the threat (e.g. pleasing, fawning, charming). Energy moves towards the threat and tries to incite the person to take care of them. The child does not develop a strong energetic core or boundaries.

Compensatory Merging – in families where it is not safe to be vulnerable, the child may develop a pattern overlay, typically the Aggressive pattern, in which they try to rescue the threat or fix the problem – often framed as “helping.” The child cannot sustain the compensatory pattern for long and eventually collapses into the Merging pattern.

Enduring - digging in, resisting, passive aggression. “You can’t make me.” Energy moves down into the ground. The child has a strong energetic core and boundaries.

Aggressive - using willpower to get their needs met in an aggressive, domineering, or charming way. Energy moves up and at the threat. The child has a strong energetic core.

Rigid - insisting on rules, order, or a “one right way.” Energy moves inward and stiffens. The child has a weak energetic core and rigid boundaries.

Most children adopt two patterns, a primary and secondary – which they choose will depend on their natural gifts and temperament, as well as their parents’ patterns (for example, if a child’s parent does the Aggressive pattern, the child who is not strong-willed might decide it’s futile to go up against a bigger, stronger adult, and thus adopt the Leaving, Merging, or Enduring patterns instead of the Aggressive pattern.)

Each safety pattern also develops into distinct gifts, which the child learns to exploit over time. For example, a child who does the Leaving pattern might become a brilliant artist or intellectual; a child who does the Aggressive pattern might become a badass CEO.

The parenting pattern trap

Any human relationship is a relationship between two people’s respective essence (who you are when you are fully present and embodied, being your essential, best self) and their patterns (the safety patterns you do when you encounter stress).

In the ideal world, a child experiences parents who are in presence most of the time. The child is thus able to template what it means to be in presence. They still develop safety patterns, but they hold them lightly.

However, since life is full of stress and challenge, most children experience parents who are often in pattern, rather than in presence. They become wounded by the patterns, and develop strong patterns in response. I call this process the Parenting Pattern Trap.

The child acts out. Young children threaten a parent’s sense of safety because children are helpless and lack self-regulation, cognitive, bodily coordination, and verbal skills. Some children cry a lot or have trouble regulating their bodies. Throughout their childhoods, they can and will “act out” in ways that cause the parent stress.

The parent reacts from childhood safety patterns. The parent reacts to these incidents using their childhood safety patterns. These might look like:

Leaving – ignoring the child’s behavior and hoping it will go away

Merging – escalating the problem by taking on the child’s problems and feelings as one’s own, trying to fix the problem, being overly indulgent or permissive. Expecting the child to meet the parents’ emotional needs.

Enduring – being sullen or negative, saying “fine” when upset, shutting down communication, accommodating the child but then complaining.

Aggressive – escalating the behavior by getting angry, criticizing, blaming, shaming, guilting, or punishing the child, e.g. “You did this on purpose.”

Rigid – imposing harsh or demanding expectations, rules and consequences. Refusing to admit when the parent made a mistake.

3. The child is wounded and responds by adopting their own safety patterns. As both the child and parent repeatedly do patterns, the child (and parent) are repeatedly wounded. In most cases, the wound is repeated, not treated.

4. The child becomes an adult The child carries their patterns into adulthood, and reproduces them in romantic and workplace relationships. Childhood patterns become entrenched if wounds are repeated and not treated. The now-adult exploits the gifts of the patterns, for example in their careers, which leads to attachment and fear of giving up the negative aspect of the pattern.

5. The adult has children. The adult has children of their own. The cycle begins again.

The biggest reason parents stay stuck in the trap is because parents in pattern react to the damage they are doing by going further into pattern. Going from being the victim to being the aggressor is awful – parents viscerally understand the child’s pain because they experienced it as children, too. The parent spirals into shame, guilt, and anxiety – causing them to double down and reproduce the same patterns again (this time, the child is not the trigger, it’s the parent’s inner critic). This can look like parents attacking and blaming themselves, dissociating, or running away from confronting and healing their patterns into work, alcohol, social media, school volunteering, and other distractions. It’s a terrible cycle, and many parents don’t realize what is happening until something calamitous happens – a child develops an eating disorder, falls into depression or self-harm, or cuts off contact.

This way out: from pattern to presence

There is a way out of this cycle. Parents can learn about their patterns, seek help in the form of therapy, couples counseling, spiritual teachers, parent education, and commit to practices that keep them in presence rather than in pattern – such as meditation, yoga, qigong, somatic practices, plant medicine, reading and listening to self-help books and podcasts, taking classes, and spending time in nature. Because patterns are unconscious and we are deeply attached to them, it takes patience and work to recognize and unlearn them. This is the process of self-realization.

It’s also never too late to break your patterns. Any time you notice yourself going into pattern, you can pause and bring yourself back to presence. And if your pattern harms your child, you acknowledge and repair the harm, and re-commit to changing your patterns for the better. Remember, patterns are things we do as parents, not who we are, and we learned them for good reason – they kept us safe.

You can help others, such as your co-parent, break their patterns by being in presence. Any relationship is like a dance. When you change your dance steps, your partner has no choice but to change theirs or leave the dance. You can never break another person’s pattern by being in pattern, only by being in presence. Often, the most liberating and challenging patterns to break are those of our own parents, who, despite their advanced age, may still be stuck in the same patterns they did when we were young. You know you have broken your own patterns when, as an adult, your parents don’t trigger you any more. Now, that’s the stuff! 😀

How patterns become stories

When a safety pattern works, it reinforces an inner story. For example, if the Leaving pattern keeps a child safe, they might tell themselves a story “I don’t belong here.” To heal, you need to direct your attention at your essence, rather than at your story. When you direct your attention towards your essence, you tune into your higher self, and you can ask yourself if a story is true or not. You can also receive insight and translate that into thought and intention, which can become a new story.

When direction attention to your essence to inquire about a story, ask the following three questions:

STEP 1: Is it mine?

Where did the story come from? Is it my story, or did I pick it up from somebody else? A story that is yours will resonate with your core in a positive way. Stories that carry a negative or self-harming charge are never yours..

STEP 2: Is it true?

The next step is to ask whether the story is true. “I’m not a writer” was simply not true for me. A true story will resonate deeply with your essence. “I am love,” “I am peace,” and “I am kind,” are examples of universally true stories.

STEP 3: Is it serving me?

If it’s motivating and encouraging you to express your potential, then it is serving you. If it’s holding you back, it’s not. Stories that serve you never harm you or others.

Telling yourself new stories

Telling new stories is not just about making up words. You actually need to feel the story with your whole body. And you need to start doing the actions that will make that story true. If I want the story “I am a writer” to be true, I have to write. In my case, I have to commit myself to getting up at 4 or 5 a.m. to write for two hours every day, and do my best to publish my Substack weekly (or in the case of more ponderous essays like this one, every two weeks!).

As Dr. Wayne Dyer notes in The Power of Intention, passion must be married with discipline – the will to learn a craft and the inspiration to experience joy while doing it. Every person’s worth is innate and not comparative. For each of us, the stories we tell are the ones that allow us to be the co-creator and hero of our own life story (link to your life is a story).

The labyrinth and the bicycle

In my experience, 10 years is a good amount of time to break the majority of your patterns and create new neural pathways in your brain. The process is like entering a labyrinth – you follow your patterns and stories and unlearn them, until you arrive home, at your center, core, or essence. You then follow the path back out into the world, the path being the practices that help you stay in your center, core, or essence.

Being consistently in presence is like riding a bicycle. It is difficult to learn – very wobbly at first – but once you get the hang of it, it becomes second nature. However, no matter how good you get, it always requires continuous attention as you take your bike on new adventures. As you ride, you need to stay aware of your balance, your surroundings, the path you are on, your destination, other cyclists, and bumps in the road in order to stay in fluid motion. Your bicycle (your body) might get a flat tire. You need tune-ups from time to time.

For the kids

If you’ve made it this far, you might be wondering: that sounds like a sh*t ton of work. Is it worth it? I’m here to say it is. As a I write this, I can honestly say that my patterns are mostly healed, and parenting has become a pleasure. I now have a great relationship with my mom, who I was not on speaking terms with for years. Seeing my kids — and the kids who read my children’s books — sparkle solidly in their presence, core, and creativity — is the stuff of dreams. There is nothing more satisfying or worthwhile than helping human beings of all ages realize their amazing potential. 💫

This is so great! I love how the safety patterns are mapped to observable behaviors. When you don’t have a framework form which to self reflect, personal growth can seem so complicated or impossible. But this is presented so clearly!

I love this framed as when in “presence” vs “pattern.” I use the Big Five and the Enneagram to observe my patterns, and this awareness of the behaviors and energy I use when I am in emotional pain has helped me become more present. Responsive vs. reactive. I didn’t have kids, which I do believe it’s the ultimate place to see our patterns in action - similar to how romantic relationships also activate our patterns. We’ve been on a similar yet very different journey, and I appreciate your awareness, insights, and deep care you’ve put into your parenting - and writing. You are most definitely a writer. 😊